Volume I. #5

WE ARE, EVEN HERE

Meanderings in Re Thinking Re Seeing Re Forming Educational Paradigms & Cultures

I am drawn to gardens, but I am no gardener. To be sure my hands have dabbled in dirt. I’ve dug and planted and replanted and hoped in and paid for fast-track miracles—those you can buy at Home Depot. Such trips and exchanges in faith, cash, and colorful granules of science, that appeared untimely snatched from a cozy life in neon tubes, were especially frequent in the early days. These youthful times of bachelorhood and neophyte gardening were often marked by efforts to will beautiful plants clearly tagged for full bright cheerful sun into small corners of town-house earth clearly taking life in shade.

During these labors to root leafy creatures in unsuitable conditions—and unconsciously ignoring the firm dark fate if place remained the same—I was earnest to protect these delicate beings. I became aware of such enemies as beetles, Japanese or otherwise, aphids, slugs, etc. And I became aware of natural allies. Formerly useless to me, creatures like ladybugs and preying mantises were seen in new affectionate light. All of this nurturing, warring, and action with metal spades went mostly unheeded by the roommates. As long as the grill, abiding in the same vicinity as the garden creatures, regularly spoke of meat and fire and exhaled curling streams of smoke carrying scents of charred hardwood, (and such things as water bills were shared and paid), all was well. But when small bowls of beer began to appear at the feet of colorful plants, well then eyebrow communication, forced coughs, and askance looks had more frequency. This was touching fanaticism if not blatant immorality—sacrificing perfectly good beer, and as a young teacher?!!

To clarify, the beer in a shallow bowl was a tip from a charitable neighbor with more experience and greener thumbs than me, and it worked! Many a morning I awoke to a stiff leopard slug, maybe two, who had taken its last uninvited bite of my plants and its last salty drink of my beer…but dead slugs or no, fate and sun had already fixed plans for those flowers. Less beer was shared with slime sliding creatures of the night in that little corner of Northern Virginia.

I’ve learned a few things since then. That reminds me—as guilt likes company (though joy likes it better)—of an adventurous friend. Chuck was an older friend and has since passed on. I miss him. He was successful by most common standards, had traveled the world, often in a giant sailboat—perhaps he didn’t pass in and out of days like Sendack’s Max, but maybe. He certainly loved wild things and was a storyteller. However, his stories tended more to speak of his failures than triumphs—such as experimenting with an old loom high up in a New York sky scraper and cracking not quite breaking a window when a piece, I don’t know which, leapt from the loom into the giant glass, but not quite into the beyond. Another story featured a bird of prey—a hawk or falcon, let’s go with falcon.

Fascinated by medieval stories of falconry, he was eager to try. But he wasn’t going to any store. On some high bluffs, maybe in Missouri, he spotted a falcon’s nest alive with an adolescent. He trekked up and with stealth and care reached down. He took it home and was determined to give this falcon the best—fresh meat every day, sometimes red sometimes white, excellent fatty cuts, no feathers, bone, or cartilage to mess with. He loved it and wanted it to thrive, and perhaps quietly desired it be one of the best to take the skies. But, it didn’t soar in blue skies or glide and dip in thermals. It didn’t, like Hopkin’s poetic Windhover, suddenly turn “As a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend” and charge through air and “big wind” giving heart-stirring displays of “Brute beauty and valour and act...” It didn’t thrive. As Chuck learned and stated matter-of-fact: it needed those nails and bones and other “useless” things to be what it was. Ah well, he’d say, and chuckle at his mistake. His kind eyes flickered a sign of ache for the bird, and his overall unspoken expression said he learned something about created things and about himself.

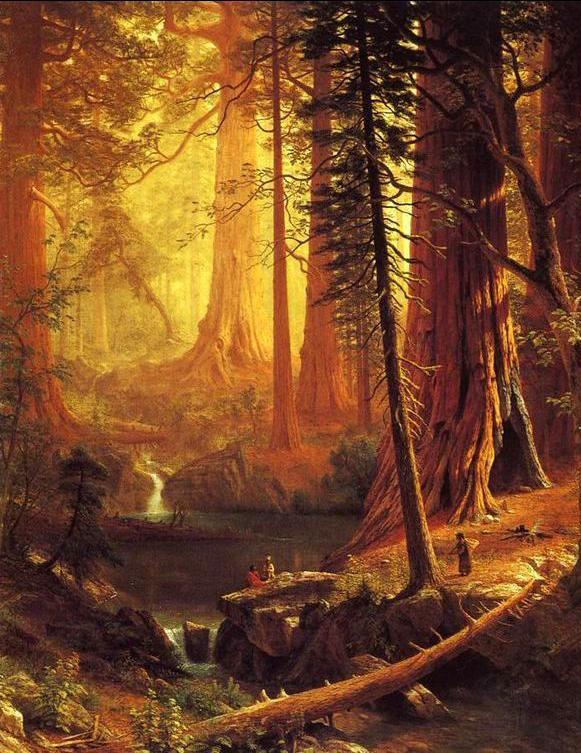

www.albertbierstadt.org

Returning to gardens, while my hands have not been as active in them as much as I’d like, I often ponder them when thinking about education or the home, and I visit them. Without doubt, the most memorable and stirring experiences have been in natural places of wild beauty. They hum with their own rhythms, cycles, and harmony. Alive with tooth, claw, and song, they give an undeniable sense of bigger, wiser, more mysterious and creative hands at work than fit typical human categories. Like most, I’ve tried to capture that beauty and that experience in a camera. And like most, I’ve found myself excusing the photo time and again: “It doesn’t capture it.” However, strangely, a work of art, whether more abstract or natural in its form, often has captured for me a variety of those invisible lines and ingredients a camera cannot, and given something close to that original experience. One such experience was a stroll amidst a grove of giant California redwoods at dusk. I have postcards and posters and photos to share and to remind me of that majestic walk. But a painting by Albert Bierstadt has best brought me back. While cultivating a like moment in the present, it sparks a nostalgia and a yearning for that past experience, and I’m moved to return and bring my children to that serene wild place.

That said, I’ve never been drawn to visit a garbage dump to experience beauty or flowers. But another artist has brought me there and I’ve often returned.

Perhaps I should say a couple artists have brought me there, as I first heard the song Even Here We Are in a version by Shawn Colvin and have since listened several times to the original version by Paul Westerberg.

Even Here We Are

Paul Westerberg

Beautiful flowers in your garden

But the most beautiful by far

The one growing wild in the garbage dump

Even here, even here we are

Even here, even here we are

Song of the bird way up in the sky

But the most beautiful by far

The scream of the man who never learnt to fly

Even here, even here we are

Even here, even here we are

Sun shines bright, it's a beautiful sight

But the most beautiful by far

Is the blind girl alone, the angel of the night

Even here, even here we are

Even here, even here we are

While both versions speak of suffering and contradictions, these contradictions burrow their way to meaningful paradox and beauty. The original version has deeper more haunting notes of loss and longing and does not return, as Colvin does, to the flower growing wild. The original also has less linking verbs and normal grammatical structure—giving a raw and unadorned sense to the images. (In a way it reminds me of some of the idiomatic language I’ve heard from many Indians who still draw deeply from their oral cultures and communicate with a heartfelt sense that is simultaneously matter-of-fact and simple).

Collectively I’m struck by the overall sense and imagery of beauty and pain, of wound and transcendent longing. We are taken to a beautiful garden, a manicured place of repose, but then transported to a garbage dump and to a flower growing “wild” there. Itself “wild” and driven by an unseen and silent “wild” source, the flower draws life from what is broken and unwanted. It is transforming it, healing it into something new. It is “beautiful by far” and somehow is.

Our eyes are taken upward to a bird in the sky, but then to a different experience of flight. We hear a cry of pain and longing from a man who had “never learned to fly”, but who, perhaps through the frustration and pain, through the wall of mortal limit, found a window, a different way “more beautiful by far.” Or perhaps simply the cry speaks of that other way.

Lastly, we look to the sun and then are taken to the dark and to a blind girl in solitude. Perhaps she has transformed her suffering and sees beauty through and past darkness. Nevertheless she is herself declared the stuff of more beautiful things, she is an “angel of the night.”

Underlying and supporting each set of paradoxical images is the refrain: “even here we are.” It is a matter-of-fact statement without anger or despair. Rather there is hope, there is a declaration of great beauty—beauty by far—and there is a sense of interior repose and unity. We are here in this tension of beauty and mess, of wings and feet of clay, of holding and beholding Beauty and All, and not holding it. And it’s ok, or more than ok.

Stepping aside from the best engagement with the song, from simply experiencing it, I think it offers much insight and food for thought with some seemingly unrelated things, such as the business of education.

It echoes the idea of Plato, and numerous other great poets and philosophers, of the wound of beauty and the inherent relationship of beauty, truth, and pain. To speak too plainly, sometimes it is the experience of profound beauty that wounds the soul and pierces an apathy or a stagnant condition, while it opens a memory of lost wholeness. As one is struck by and yearns for the beautiful, it reveals the existential wounds and absences, the lack of fulfillment deep within the self, and the need for transformative gift to somehow attain it. This experience with the Beautiful unveils as it ignites primal desires (eros) for transcendent things. Reversely, as thinkers like Victor Frankl have observed, at times it is the experience of profound suffering that ignites the inner eyes, burns past more basic appetites and physical comforts, and sheds light on the deep and natural desires for transcendent things and ultimate fulfillment.

This is at the center of Frankl’s famous work, Man’s Search for Meaning, which draws from the Austrian psychiatrist’s harrowing experiences in German prison camps, including Auschwitz. Not with the eyes of a distant clinician, he beheld and felt the horrors within and without. He observed those destroyed by the dehumanizing experiences, even if they physically survived. And he saw those who mysteriously kept their selves through heroic endurance and patience, but through more than that. In them and in himself, he observed the intensification of spiritual life, including silent experiences of heart-stirred and stirring contemplation, a sharpened sensitivity to beauty, and an enlarged capacity for love and affirmation. He saw that suffering itself contained meaning. This insight into meaning transcended the grey gloom, the day after day pounding of physical deprivations and pain, but more so the psychological trauma of being viewed and treated as a nameless number, as a soulless piece of utility. Here he speaks of a moment on a train with other prisoners:

As the inner life of the prisoner tended to become more intense, he also

experienced the beauty of art and nature as never before…If someone had

seen our faces on the journey from Auschwitz to a Bavarian camp as we

beheld the mountains of Salzburg with their summits glowing in the sunset,

through the little barred windows of the prison carriage, he would never have believed that those were the faces of men who had given up all hope of life and liberty…

and of his own epiphanies:

A thought transfixed me: for the first time in my life I saw the truth as it is set

into song by so many poets, proclaimed as the final wisdom by so many thinkers. The Truth—that love is the ultimate and the highest goal to which man can aspire…I understood how a man who has nothing left in this world still may know bliss, be it only for a brief moment, in the contemplation of his beloved…

Another time we were at work in a trench. The dawn was grey

around us; grey was the sky above; grey the snow in the pale light of dawn;

grey the rags in which my fellow prisoners were clad, and grey their faces…

I was struggling to find the reason for my sufferings, my slow dying. In a last

violent protest against the hopelessness of imminent death, I sensed my spirit piercing through the enveloping gloom. I felt it transcend that hopeless, meaningless world, and from somewhere I heard a victorious “Yes” in answer to my question of the existence of an ultimate purpose. At that moment a light was lit in a distant farmhouse, which stood on the horizon as if painted there…”Et lux in tenebris lucet”—and the light shineth in the darkness.

Certainly these circumstances are extreme and a garbage dump is not quite the paradigm we want to envision when thinking of schools. But there are profound human lessons here and things to remember, especially when we think of those institutions and places in which many of our children spend the prime time of their days and the prime time of their young formative lives. Here we can only meander and touch on a few general points, ask a few questions, and hopefully set the stage for future works and meaningful conversations.

Ending and Beginning with Persons

Do we plan, do we operate schools based on a whole vision of the person, beginning with the recognition of the transcendent desire for meaning, beauty, and liberty in the heart of each person? Do we cultivate the conditions, dispositions, and cultures that give rise to authentic, personal growth and fulfillment? Do we truly allow the deeper parts of the self and spirit to exercise and breathe?

Almost every school talks about the whole person in its mission, often has an image of a heart, tapes up “inspirational” posters with words like “joy!” and “wonder!” and features posed photos of bright children and bright days. But how well do we tend to the sources that give rise to bright faces and real experiences of such things as inspiration, the joy of learning, and wonder whether in the sense of curiosity or in the better sense of apprehending the beauty and marvel of something? Such things can’t be prescribed or dictated; conditions and dispositions can be cultivated.

How much time and space do we give for engagements with beauty, especially with transcendent beauty as possibly apprehended in nature, in works of art, in stories, in poetry and song, etc.? Do we cultivate the kind of engagements that can touch the heart, the emotions and imaginations? Do we regard such things as “useless” and unimportant? (as opposed to “useless” and liberating and of ultimate and deep importance)

How much time and space do we give for reflective silence or for meaningful engagement with questions of the spirit, of faith, and the bigger why’s of life?

All’s not Well That Ends Well

Schools of all sorts overflow with pressures for clear, measurable and often quick results, whether academic, athletic, or with respect to character. It is easy to confuse means, such as order and discipline, for ends. It is easy and tempting to short-change process. Examples of all sorts abound, but one that sticks in my memory involves my eldest daughter. Having moved, my wife was registering her at a new school. While doing so a young female student burst into the office and declared to the secretary that she had something to write in the “good book.” Delighted, the secretary asked what good deed it was. The child answered something like, “I was quiet in class and I told the truth.” The secretary gave an enthusiastic smile and with affection and feeling said, “Oh yes, it is important to be quiet and to tell the truth!” She then opened the book for the holy inscription. Such rewards and systems, with all their warm feelings and intentions, encourage the result and corrupt its natural source—they unknowingly cultivate quiet attitudes of self-righteousness, self-centeredness and moralistic judgments rather than a loving, authentic and magnanimous heart.

Such efforts bring short-term effects and they may look good, but even the short-term effects have to be questioned, let alone the long-term ones. We also have to ask: are these efforts truly for the sake of a child’s growth or more for the sake of the adults and school managers’ security and sense of achievement?

With respect to many things, from academics, sports, to behavior, religion, and the unconscious perception of the ultimate order of things: is love or fear the primary motivator? Is love or fear the primary result?

Pain as Pathway

Pain is unavoidable and is certainly part of any educational experience. In unhealthy ways it can be experienced in overtaxing analytical aspects of the intellect and not exercising the more receptive, intuitive aspects or the emotions and imagination. There can be frustration especially as a student may feel he is being “tuned” as a machine and not as a dynamic person with needs for such things as nature, play, wonder, (reasonable) risks, exercise of choice and freedom, and growing from failures—in addition to discipline and skills. (The massive amounts of medication consumed by American boys point to issues beyond their own chemical constitution). And, of course, in the wise Aristotelian sense, there can be excessive avoidance of certain pains and challenges and a cultivation of comfort seeking and softness, which lead to prolonged future pain experienced by a weak and poorly-actualized adult.

Difficult growth, any “getting to the next level” or going deeper necessarily crosses bridges of pain, whether it’s simply an athlete or a writer or any person recognizing “garbage” and goodness within and seeking to improve. Such pains, or crosses, or bridges can lead to better joys and better pleasures and higher levels of fulfillment. Hopefully, in one degree or another (but not in the same particular way), they can lead to discoveries and a vision like that of Victor Frankl. We have to ask ourselves: do we cultivate the experience of the right kind of pains? Do we give the freedom and space and careful guidance for those pains to be experienced and the growth to happen? Do we encourage personal discovery and good dispositions more than mere compliance and obedience? Do we have an eye for strong long-term growth seasoned by risk, successes and failures, and not just easy, often impersonal, short-term compliance?

Headless Horsemen and Lanterns

Educational institutions are some of the most systemically and relationally complex organizations that exist. They require intelligent and capable managers and leaders with vision—those who can shine a light for the managers so they are not like headless horsemen while running an organization. Do we do enough to attract and cultivate them, especially leaders? Are not many institutions dominated by managers who often are insensitive to such things as process and are in excessive need of security and control? Are not educational paradigms often conscious or unconscious images of well-oiled machines and factories with interchangeable technicians? More appropriate paradigms include gardens containing living things, a touch and source of wild, and gardeners who understand the dynamic of the whole garden and work as cooperative artists—such gardeners are vital for a healthy culture and should not easily come and go.

So often this issue of a deficiency in leadership can reflect on budgets and school boards who may prefer managers whom they can control and whom can be justified as “humble.” But this in itself is symptomatic of pervasive cultural views of education and educators. Conscious Capitalism features excellent reflections on leadership and management, and that section is worth a thorough read. Here is a taste:

Leaders are high-level architects, builders, and remodelers of the system, while managers ensure that the system works smoothly…Leaders have an inherent systemic sensitivity…Managers do not make history; conscious leaders do. They imagine and bring into existence that which did not exist before and which most thought could not be done.

Enough for now…until then…

Jeff

© 2019 Samuel & Erasmus institute • All Rights Reserved

SEi is a Federal 501 (c) (3) tax exempt public charity. Contributions are tax deductible.